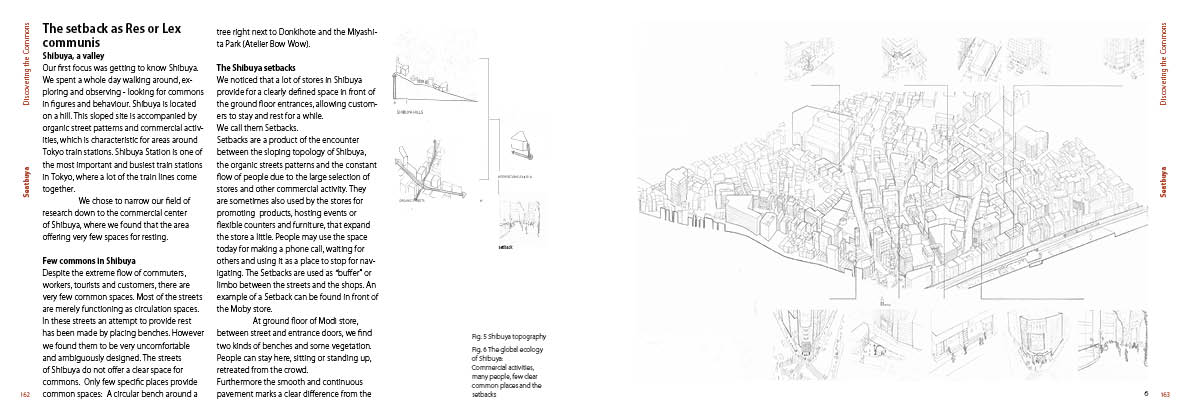

Izakaya

Izakaya was not considered as essential work during the covid-19 pandemic. Considering the change of working lifestyle such as working remotely from their houses, we have focused on the residential area. Researching the typologies of the Izakaya, we noticed the binary division between Primary and Tertiary industries. The selected residential area, Ookayama has many plum trees, which can be used for the production of Umeshu. This can help to dissolve the binary. According to the architectural typologies, we propose three types of new Izakaya combining with plum production: A: movable Izakaya kitchen car, B: Izakaya taxi which connect to the urban mobility, C: Izakaya park which has relationship with the outside.

Baladin

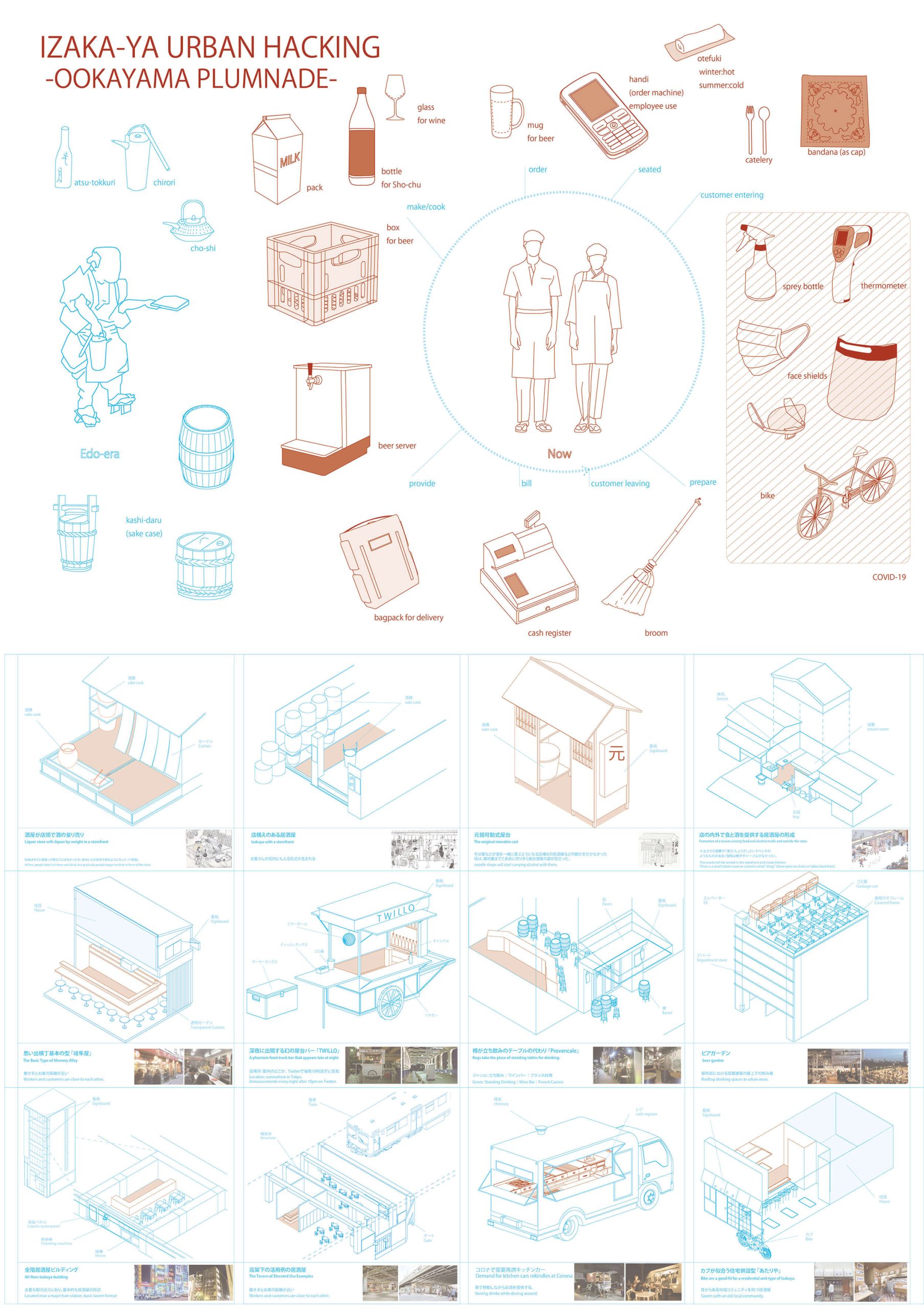

House in Uehara / Kazuo SHINOHARA

Sleeping With Art

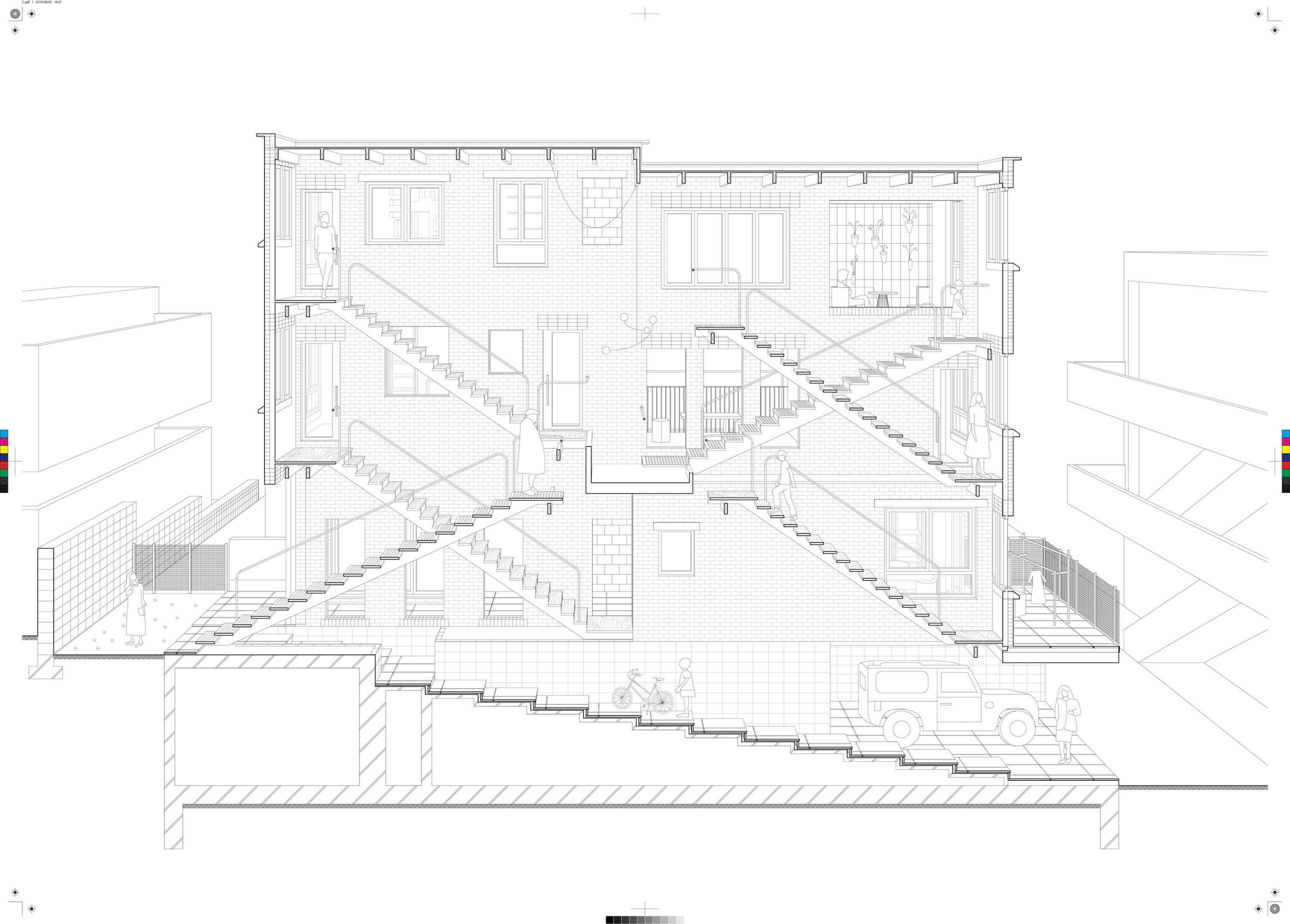

THE NIGHT SPENT WITH ART

The project is a proposal for an art complex containing an exhibition hall, a visiting artist residence, a café, a sculpture park and three art accomodation units. The site is a parking lot located in a busy area of Jiyugaoka, fac- ing one of the main shopping streets. The part facing the main road is occupied by an old tra- ditional wooden japanese house accompanied by big old trees which are `hiding` the inner part of the site where accomodations are lo- cated and create a quiet lagoon in the middle of this busy district.

The main concept of the proposal is to high- light the cultural history of Jiyugaoka and al- low visitors to experience art from a different perspective, that is to say the opportunity to spend the night together with art.

The artist residence connected to the exhibi- tion hall provides a special experience where the artist can be seen working at the time of ongoing exhibition.

During the day, the accomodations are open to the public as part of the sculpture park. During the night the units, designed to have their own private `gardens` transforms from

exhibition units to accomodating ones.

This transformation was one of the main focus points during the design process of the pro- posal.

The location of the site, disposition of the units on site in a sequence gradually opening up and the fact of unexpected usage of these units re- flects the head theme of unpredictability.

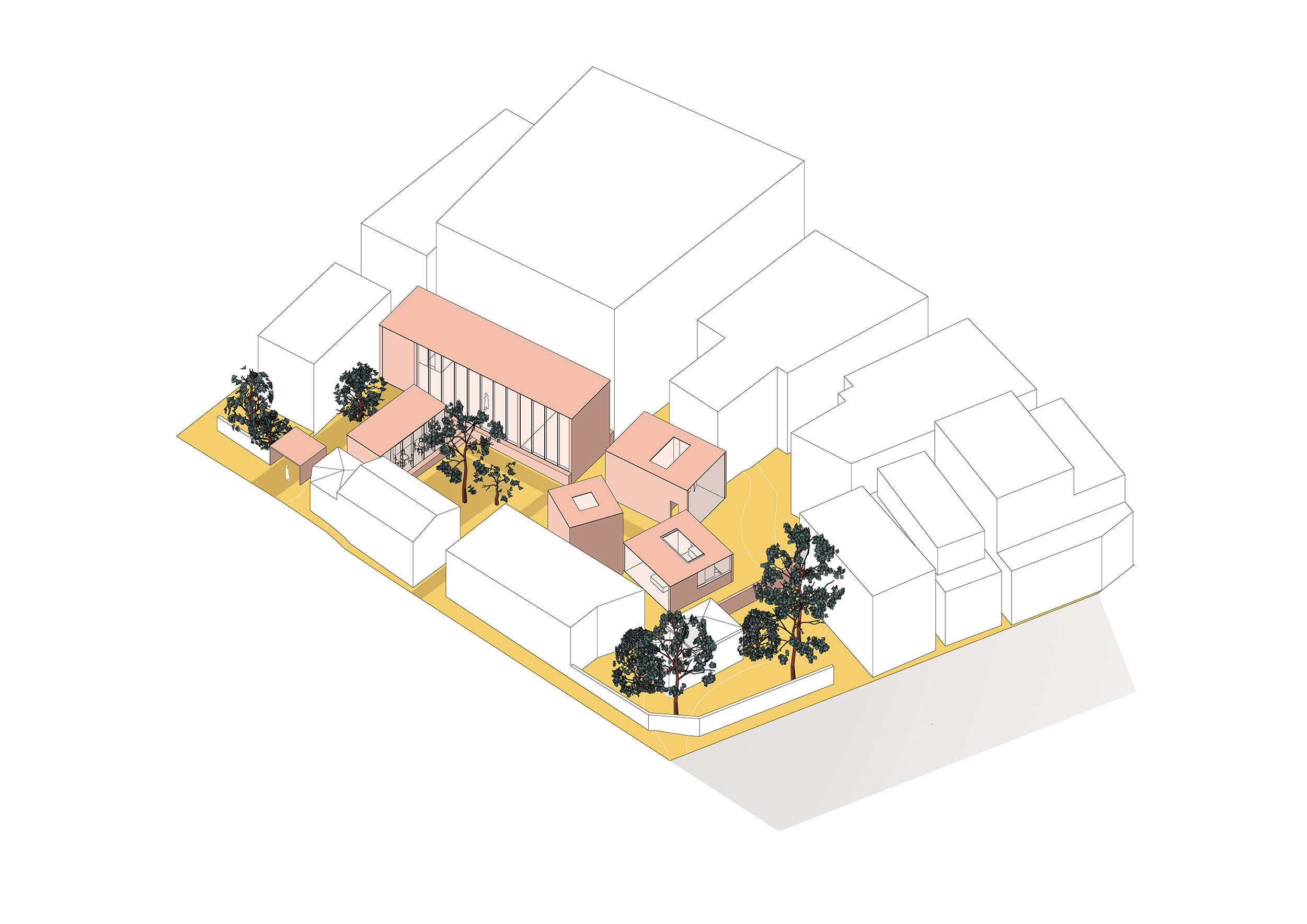

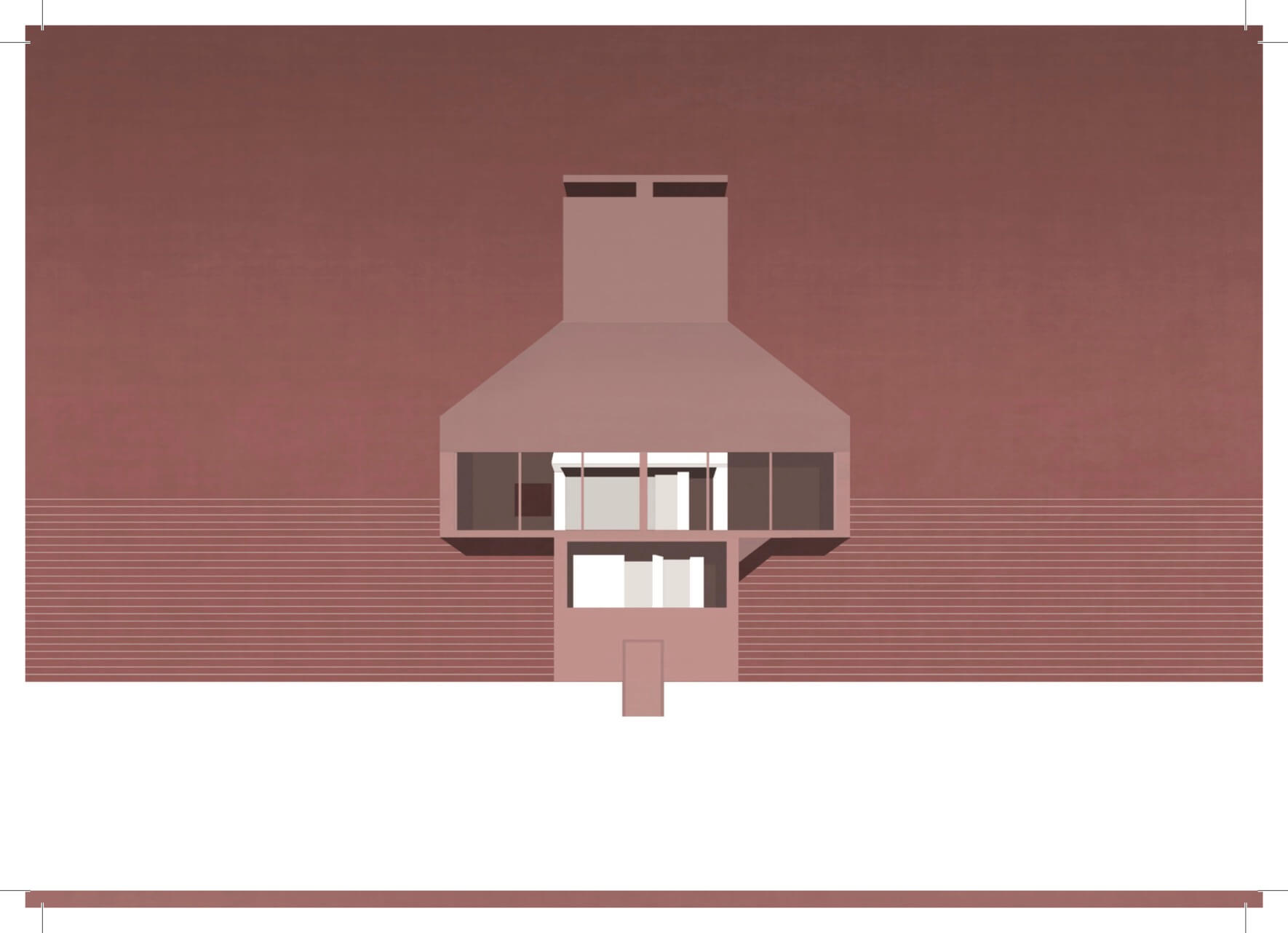

Frug House

Both the Frog House and the Gae House played important roles in shaping our design. Generally speking, these two projects can be respectively described as either a chimney with two facades or else a building with a big roof.

The main concept from the Frug House is its ambiguity, with its two facades, or faces. One on these is symmetrical and open, with large “eyes”, and the other is dug-in and shows the complex interior of the house with its various shapes and materials. Both these faces are emphasized in our perspectives. The chimney is kept because of its important position in the Frug House as well as for the design limitations and possibilities it creates. Our idea of a big roof is connected with Bow-Wow’s Gae House. Here, the roof pitch was determined by local regulations in this mostly residential area. The large-size front window makes the house more difficult to “perceive”, and this idea can be traced in both the Frug House and the Gae House.

The foursquare plan derives from the traditional Japanese “ta” character for the shape of a rice field; it consists of a simple division of the square-shaped plan into four equal quadrants. Both staircase and chimney are set in the same quadrant, forcing the stairs to dance round the chimney on the way up or down.

In our pespectives we reveal the ambiguity of our design. The symmetrical facade with its large window and hat-like roof that imitates a typical house shape dominates the first one. The second shows the playful asymmetrical backside.