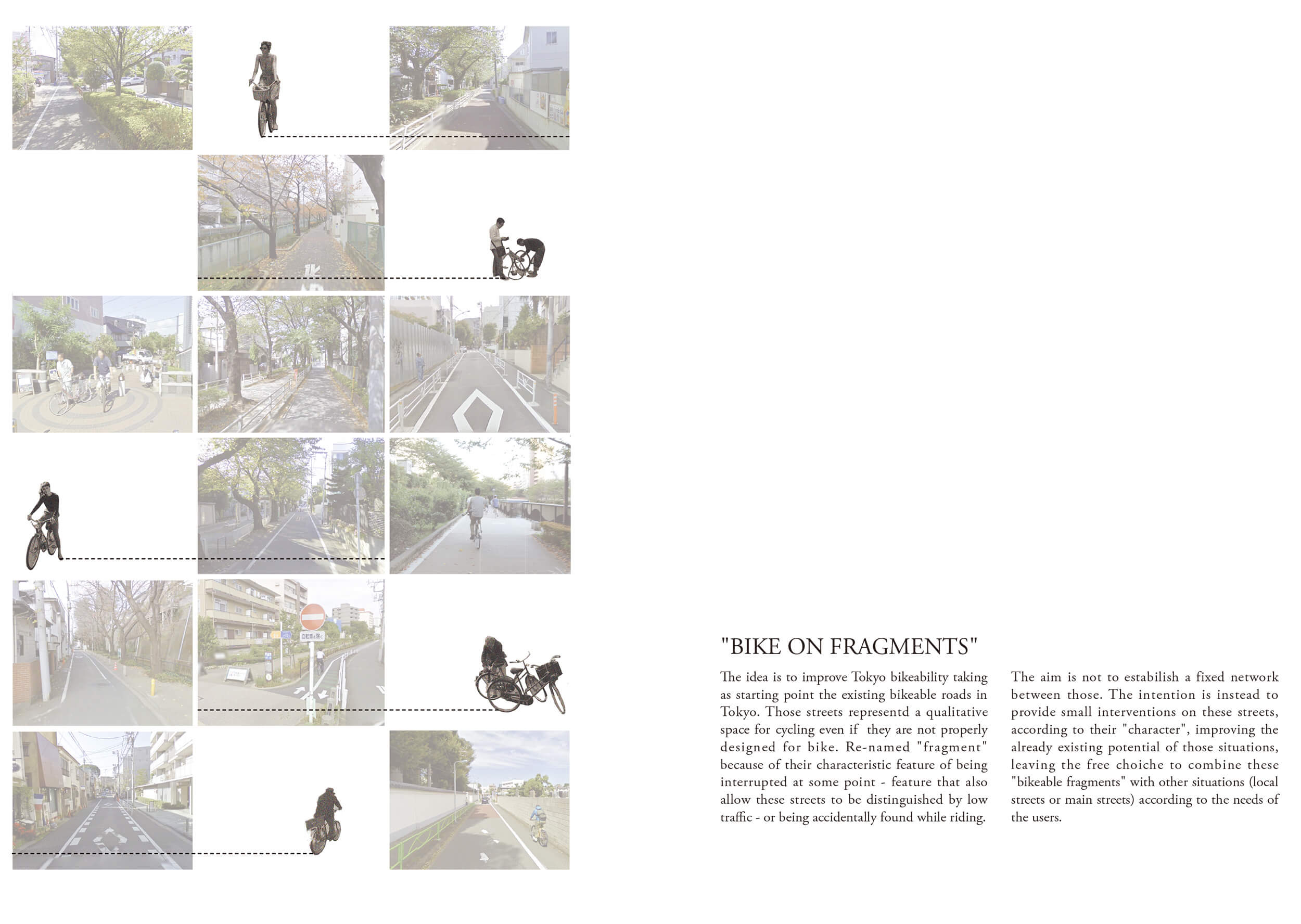

The idea is to improve Tokyo bikeability taking as starting point the existing bikeable roads in Tokyo. Those streets represented a qualitative designed for bike. Re-named “fragment” because of their characteristic feature if being interrupted at some point – feature that also allow these streets to be distinguished by low traffic – or being accidentally found while riding. The aim is not to establish a fixed network between those. The intention is instead to provide small interventions on these streets, according existing potential of those situations, leaving the free choice to combine these “bikeable fragments” with other situations (local streets or main streets) according to the needs of the users.

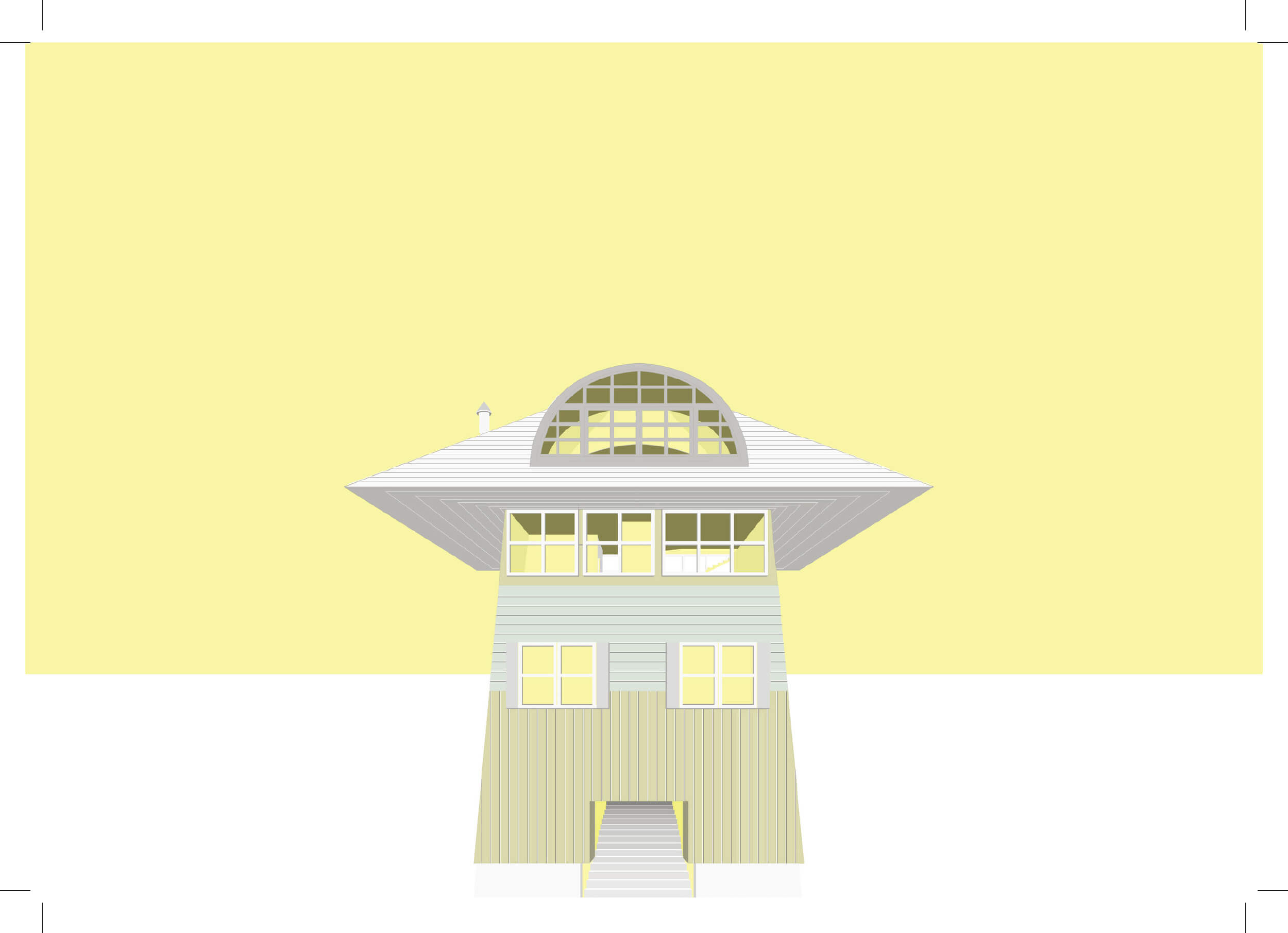

House in Vail

The House in Vail, CO, is proof that complexity and contradiction lead to ambiguity and richness of meaning. It consists of two different sorts of verticality: one articulated via the site context, the other contained by a sheer surface. North and south elevations are totally different, and the perception of the house from outside and inside is likewise contradictory. The scale of the roof and façade elements contributes to perceptual ambiguity- the real height is never directly revealed. Inside, depending on the height at which the observer is positioned, the house is perceived as either a tower or a small studio. By playing on this characteristic, while keeping the Tokyo context in mind, our new proposal suggests a building, divided into two parts, with mixed functions linked by an out of scale stair and a bridge that also inflates the perceived scale.

From the road, the entry is ambiguous, for there is no door in the main façade. Instead, it is located at the back. On the front left-hand side, a big stair emerges and continues along the whole site, as well as inside the building. It is the connection between the single parts of the house and its more unified surface that make it a whole. The outside is a semi-public space. Also, the way in which each external part is expressed separately does not encourage any visual connection with what is going on inside.

The difference between the House in Vail and our de sign lies in the act of traversal. In the former, the occupant or visitor must decide whether to take the stairs or the bridge. The new design proposes an architectural promenade, using both these elements as a continuous passage though the site. Robert Venturi’s so-called inclusive design method has promoted our understanding of the design and its articulation.

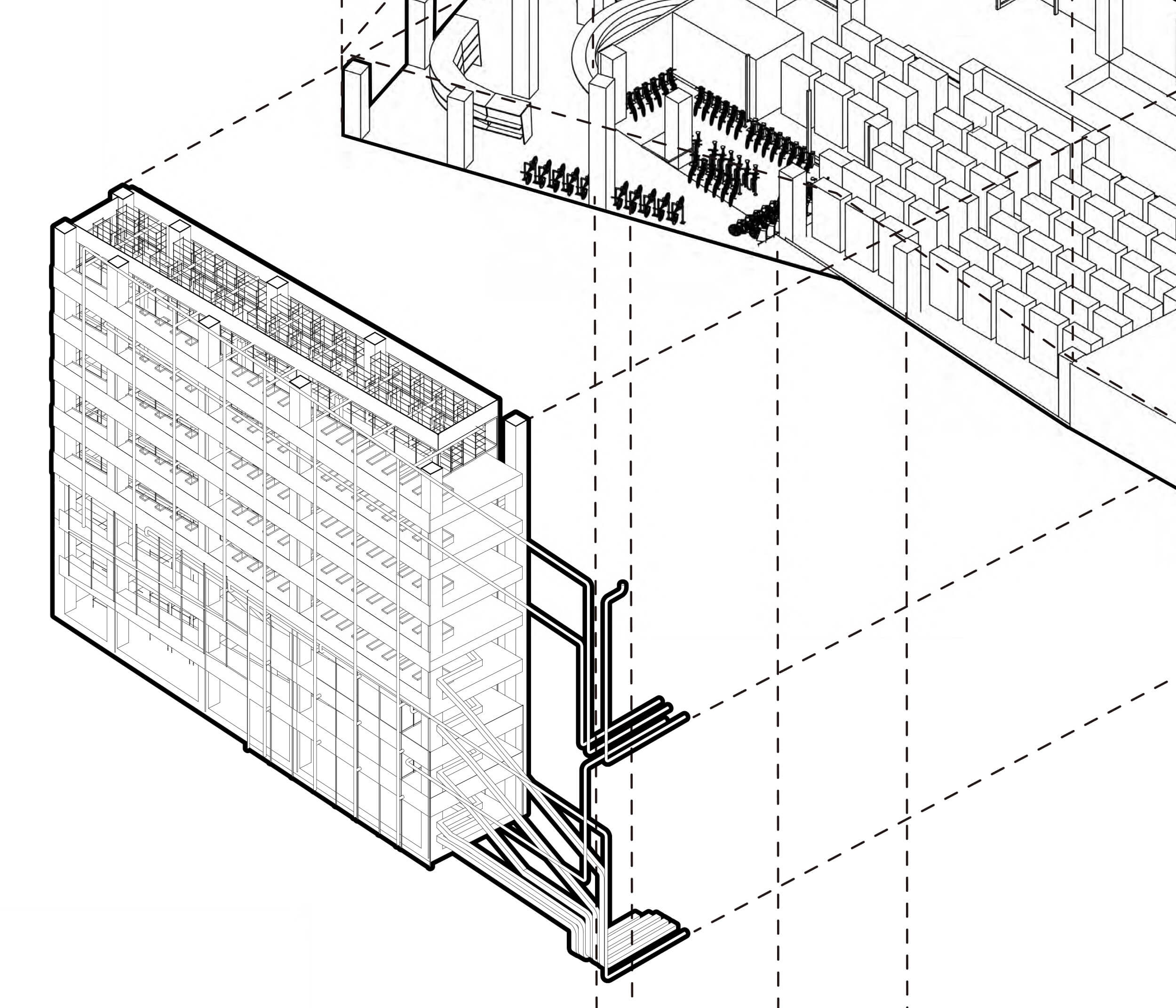

VERTICAL FARM

LIVELIHOOD UPROOTED, COMMONS EMACIATED

My mother has a vegetable garden as a hobby while she works. Amagasaki’s grandfather also makes a living from farming. There is a fundamental joy of life, as if one is rooted in the land through plants. However, in a capitalist society, there is more than that. When the logic of capital is brought into the business of hobbies to an excessive degree, our live- lihood becomes labor, and we are “uprooted “1. The healthy ecology, that is, The linkage between the “public,” “private,” and the “commons” which was supported by the layers of nature, has been bloated and destroyed by the influx of com- modified goods and service substitutes2 (Fig. 1). Production has been black-boxed by industry, and the commons and our convivial joy rooted in it have been emaciated.

DISCONNECTION BETWEEN HOBBY-LIKE PRODUCTION AND CONSUMPTION IN IKEBUKURO

We can also see this effect in the behavior of the city we observed in Ikebukuro. For example, we can see that one of the buildings has gardening plants growing out of the building, and on the other side, there is a Halal restaurant (Fig. 2), but even if vegetables are growing in the garden, they are not eaten in the restaurant next door. In Ikebukuro, you can see many gardens, but even if there are vegetables nearby, you cannot eat them. In Ikebukuro, there is a com- plete disconnect between consumption and the production of individual skills, even though they are often adjacent to each other. Architecture must become the infrastructure that connects the desire for the pleasure of growing plants with consumption, making plants com mon and creating a small cycle.

STRATEGY FOR CITY FARMING COMMONS

How can this be achieved in cities? For the commons to be powerful in a city where everything is large, it needs a broader coalition than it has in rural areas. In terms of skill level, the number of core members may not be that differ- ent from the practice in rural areas, but the amount of par- ticipants and observers3 should be much larger. Therefore, there is a serious problem with the quantity of vegetables. In addition to root vegetables that can only be grown in soil, those that can be grown hydroponically can be grown using the vertical farming method, making it possible to grow enough vegetables for about 120,000 meals4.

OPEN TECHNOLOGY AND SMALL CIRCULATION

Agriculture is becoming a very high-tech industry today5. Vertical farming is one of the best examples. Temperature, water composition, and genetics are completely regulated by artificial intelligence. The harvesting and maintenance is largely mechanized, and humans watch it on iPads. In this project, it is necessary to diagnose and anatomize vertical farming, rather than operating it as such a manipulative and closed technology, and to recombine it into a more open technology for conviviality6. It is not just a matter of making high-tech low-tech; it is a matter of reconfigur- ing technology so that it can be maintained and managed without the politics and power of control and manipula- tion that separate us from the plants. The agricultural pipes used in plastic greenhouses should be used as a framework, and the components should be as simple as possible. The growing environment should not be controlled discretely by microcomputers on a unit-by-unit basis, but rather by conventional air conditioning technology and circulation throughout the building. The technology is a key in the whole system, in which the water from the spring becomes the circulating water for the water-cooled heat pump chiller, which gradually returns to the same temperature as the environment within the building, and then returns to the environment through transpiration by the plants.

DEPARTMENT STORE REVOLVES, FAÇADE REVOLVES

When a department store is weighted according to the com- mercial value of its homogeneous structure, the spectacular intersections and avenues become the front, and the rest the back. Instead, the next generation of department stores will look to the abundant resources around them – in this case, gardening skills, water, sun, and wind – and bring the place of production back to your neighborhood. In this way, the sunny south of the building will be penetrated by the di- mension of plants, creating a new façade where production and circulation can be seen.

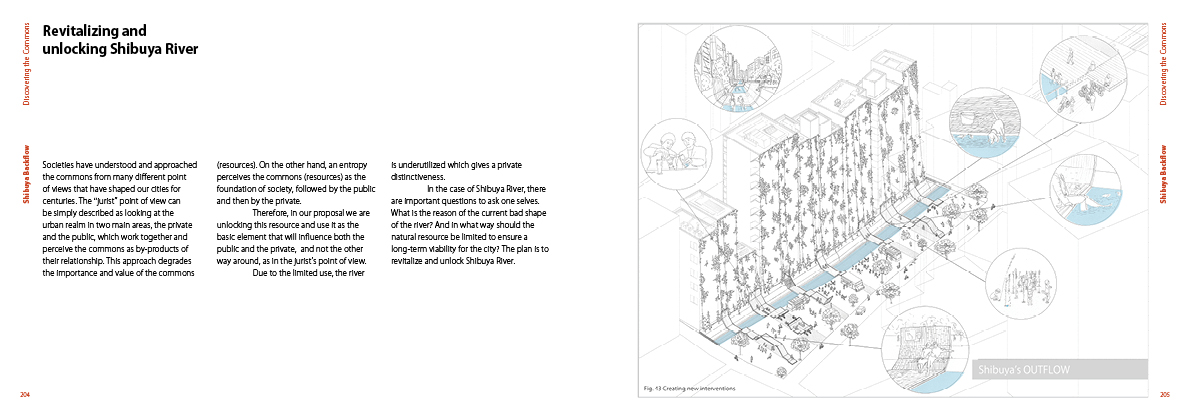

Shibuya Backflow

Societies have understood and approached the commons from many different point of views that have shaped our cities for centuries. The ʻʻjuristʼʼ point of view can be simply described as looking at the urban realm in two main areas, the private and the public, which work together and perceive the commons as by-products of their relationship. This approach degrades the importance and value of the commons (resources). On the other hand, an entropy perceives the commons (resources) as the foundation of society, followed by the public and then by the private. Therefore, in our proposal we are unlocking this resource and use it as the basic element that will influence both the public and the private, and not the other way around, as in the juristʼs point of view. Due to the limited use, the river is underutilized which gives a private distinctiveness. In the case of Shibuya River, there are important questions to ask one selves. What is the reason of the current bad shape of the river? And in what way should the natural resource be limited to ensure a long-term viability for the city? The plan is to revitalize and unlock Shibuya River.