MORI IN JIYUGAOKA

During the mapping of the various activities, we found that Jiyugaoka has a very season- al characteristic. The areas change over time, from morning to evening during the day and from weekdays to weekends.

Jiyugaoka is known for its trendy, fancy and cute shops and cafe’s that are targeted more towards the women and yet promise to offer a quality ‘Den-en-chofu’ lifestyle to its residents.

In our study, we found that there are not that many gardens or green spaces and this inspired us to create an accommodation that allows one to ‘escape’ into a ‘forest’ in the heart of Jiyugaoka.

The design is an accommodation that personifies ‘living in the forest’. It amplifies luxury living in Jiyugaoka and gives its visitors a feeling of sleeping amidst the trees and isolation in the otherwise crowded surroundings. Through our design we wish to bring back this feeling, to show how import- ant it is to get lost in these experiences and just get away from all the hustle and bustle of everyday life and enjoy the solitude while im- mersed in green.

Student: Xiaowei Wei

Genkan

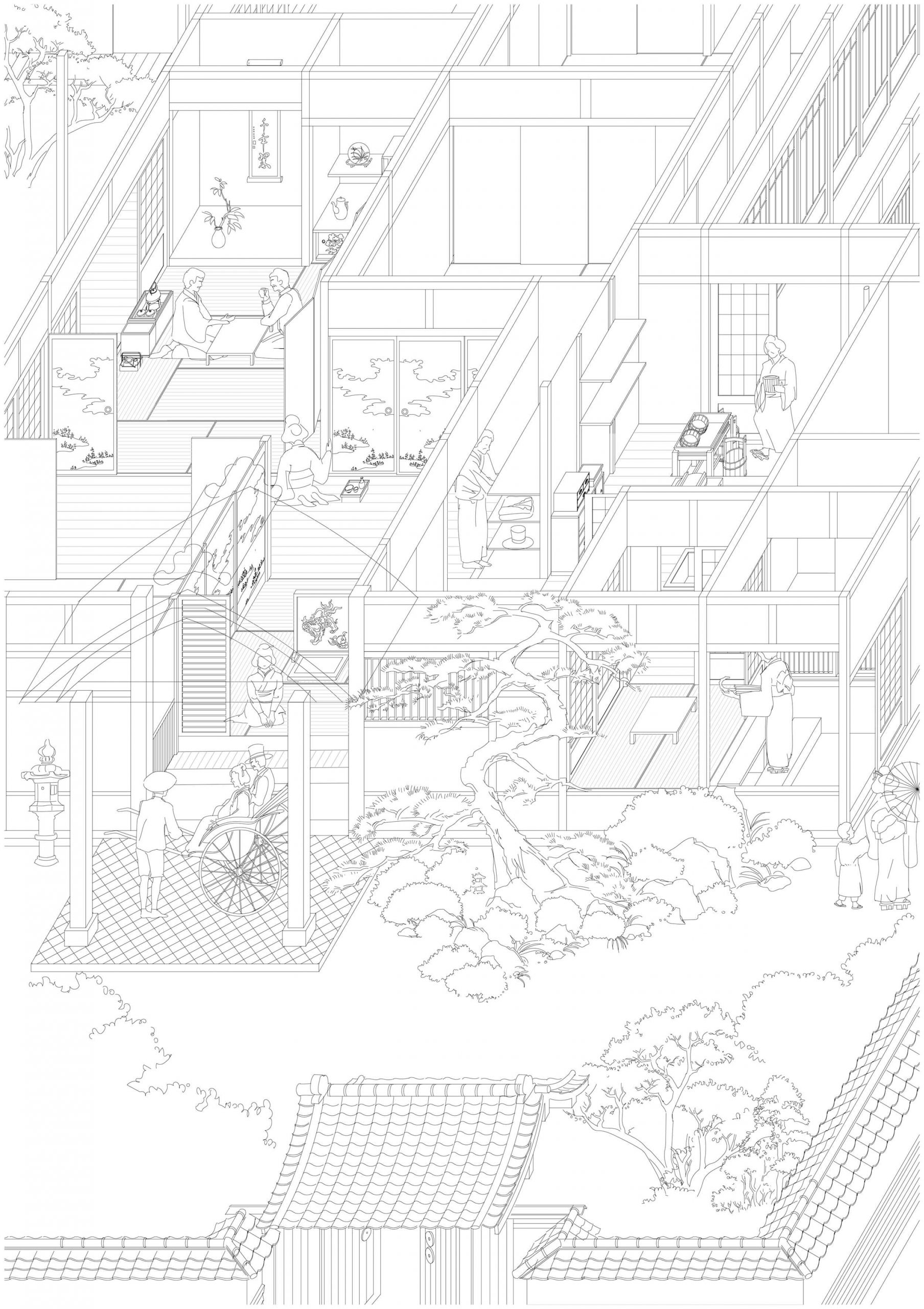

From the Meji Period to today the genkan (a Japanese house-entry-cum-doormat) has evolved from a space of etiquette to a functionalistic space, and nowadays to a space of convenience. In the Meji Period a representative house had three entrances with a front genkan (表玄関), an inner genkan (内玄関), and a katteguchi (an outside connecting door) in the kitchen, reflecting the different social statuses of the master, family members, and servants. Etiquette required a long spatial sequence from the main entrance to the reception rooms, carefully designed and staging the best views to the garden. In post-war apartment houses the traditional design of the genkan was simplified to make it a compact space containing various functions such as storage, washing, receiving goods, or making phone calls. In essence it is designed as a public space inside an apartment. However, in contemporary high-rise residential buildings the boundary between the private interior and the public exterior has been overly stretched by the introduction of common entrance lobbies where guests can be welcomed on the ground floor. Moreover, a series of technical devices, such as cameras, sensors, automatic doors, elevators, and intercoms, have been introduced for security, accessibility, and comfort, again physically lengthening the distance to the private door to an even greater extent.

Genkan

The genkan serves as a physical and symbolic threshold of the house. Differing in its position, its geometry, its sunken level, sometimes also in its flooring material, from the other spaces of the house, it is nonetheless firmly situated inside the house. Similarly, it is in the genkan that the rites of passage from inside to outside, from private to public and vice-versa, are performed—where messages are transmitted, outdoor garments and shoes are taken off, strangers are welcomed or turned away. These rites are reflected in the changing behaviors of the visitors as well as of the residents performed at the genkan, where personal feelings in front of each other are hidden behind a required formalism, yet are correspondingly revealed once the doors have been closed.