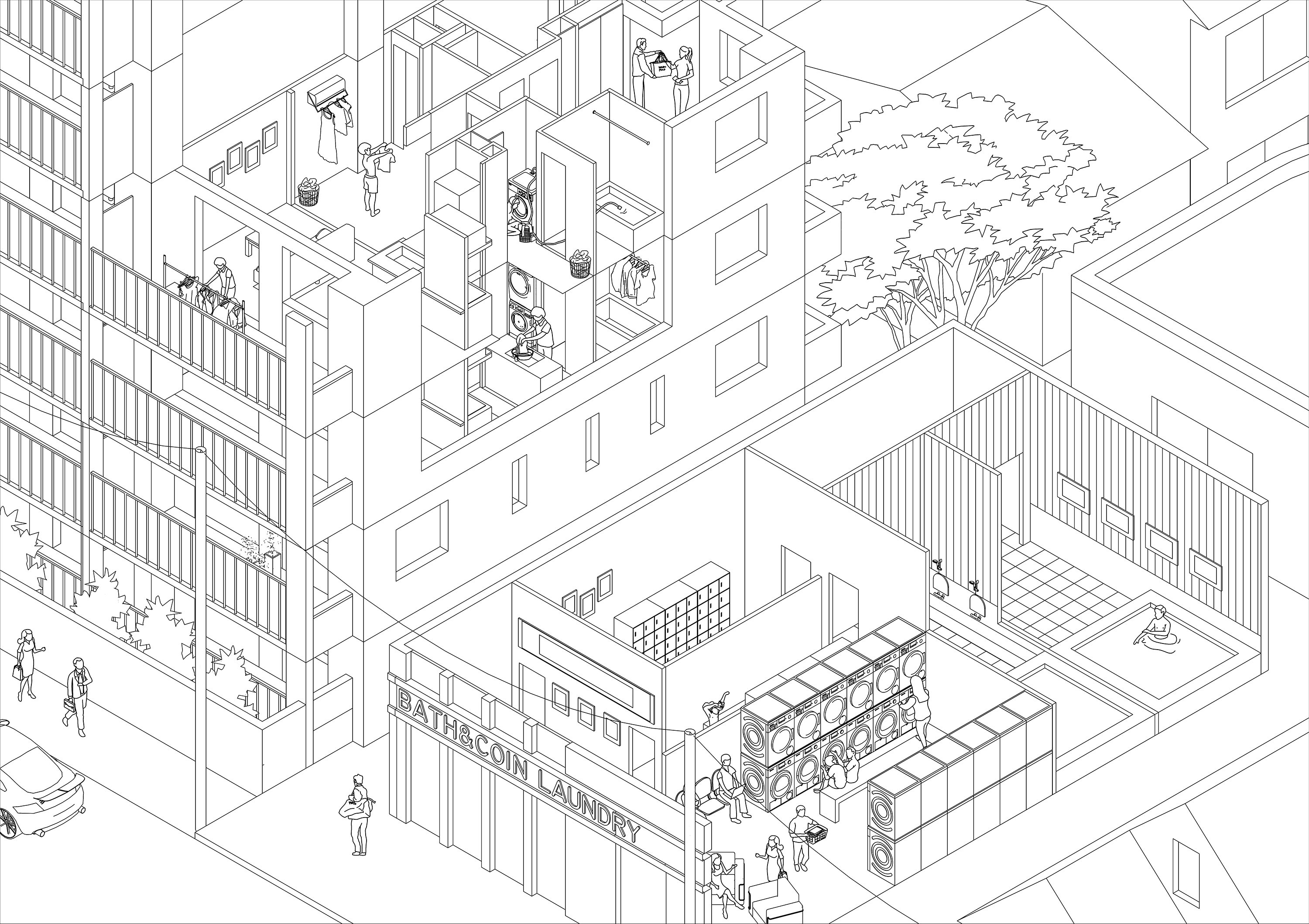

The importance of laundry as a part of Japanese everyday life has steadily declined, mainly due to the reduction of the time, space, and tools required to perform this household task. This development has not only been caused by technical progress, such as the introduction of electrical washing machines and dryers, but also by demographic and societal developments, in particular the changing role of women in Japanese society. Even though the appearance of coin-operated launderettes in the post-war years, combined sometimes with public baths, introduced a new form of communality, overall the collective aspect of doing laundry chores has decreased drastically from the pre-modern period to the present. Today washing activity is split between a variety of laundry settings and forms, ranging—dependent on the residential environments that coexist in contemporary Japanese society—from minimal washing units, to the use of balconies or bathroom dehumidifiers for drying, to communal spaces.

Teacher: Laurent Stalder

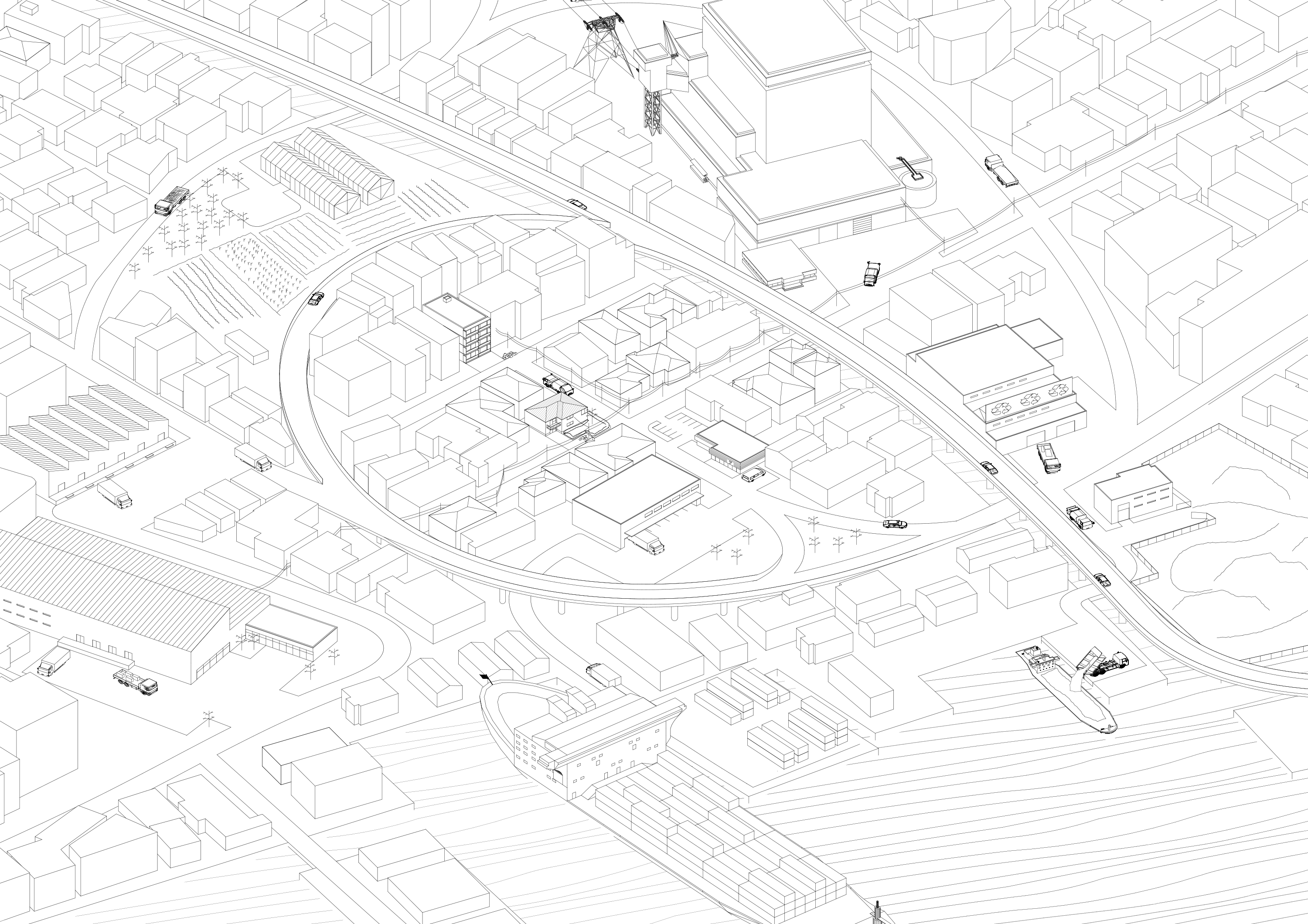

Waste Disposal

While in the early Meji Period the disposal of waste was part of a spatially limited and circular network, linking agricultural fields with markets and houses, and from there, when not recycled, again to the fields, the economic and demographic growth of the post-war period, especially in Tokyo, saw the introduction of public waste collection, primarily disposed of in landfills. This unilinear processing from production to consumption began to be increasingly called into question, starting in the mid-1980’s with the introduction of a new recycling system involving an evermore refined rubbish separation for recyclable goods, the exploitation of mix-waste for energy in large power stations, and hazardous waste being exported and reprocessed overseas. The waste-management system has thus evolved into a large, complex, and sometimes invisible chain involving multiple actors. Waste is no longer perceived as either a purely homogenous and useful resource or solely as landfill material, but rather as consisting of different constituents with varying values and repurposing potentials.

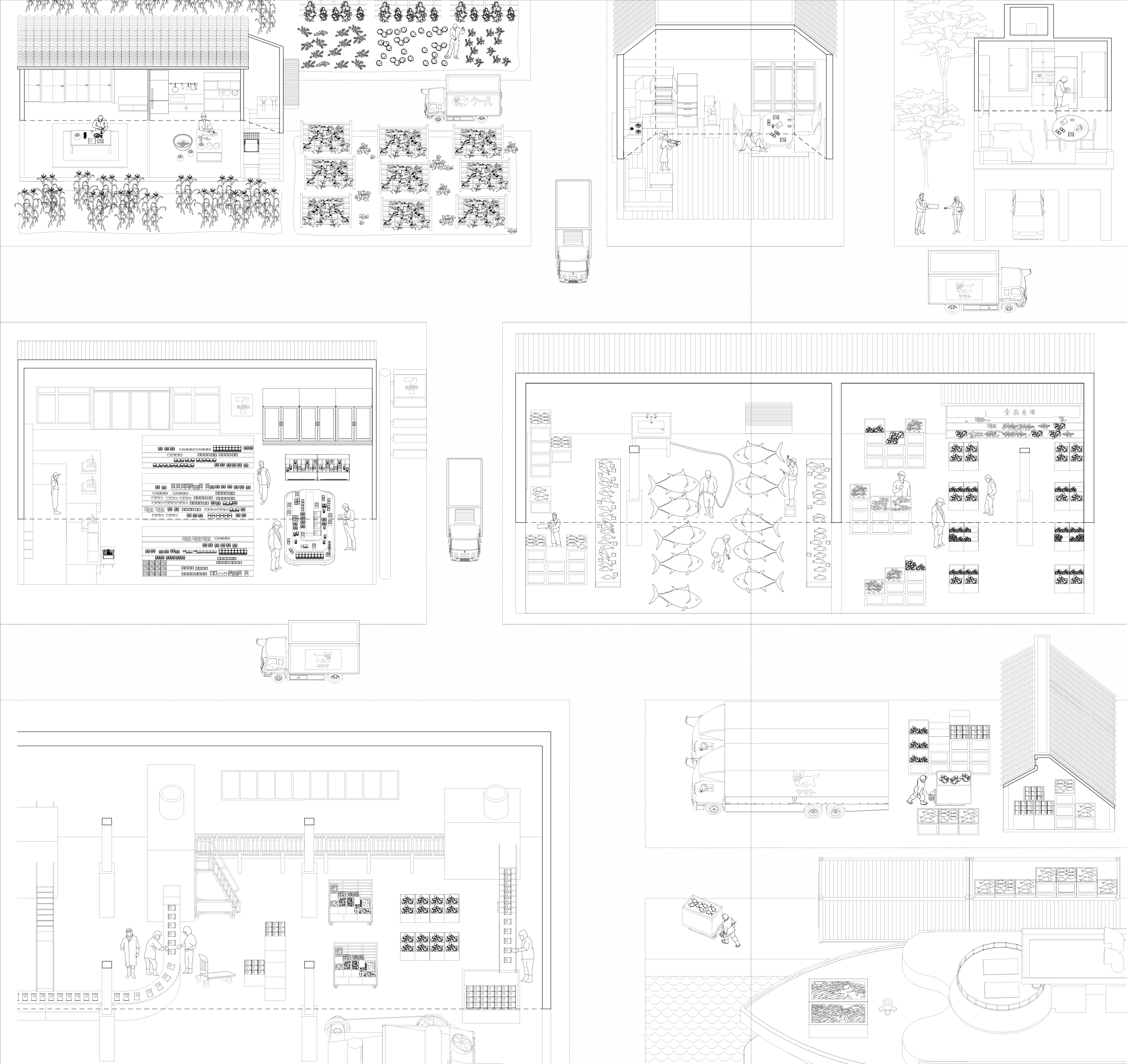

Fridge

The history of food preservation throughout the last century-and-a-half reveals the key role refrigeration techniques have played in the development of an ever-expanding food network, in the process replacing a range of traditional preservation techniques by a single purely technical one. Cooling with ice, if available at all, remained the privilege of the more wealthy until the Meji Period, meaning that most food was either consumed rapidly or preserved by a whole range of methods, such as curing, salting, pickling, smoking, fermenting or drying. With the instalment of iceboxes and the dissemination of the electric fridge in the 1950s, food purchased fresh from the market, and from the 1960s on in supermarket chains equipped with refrigerators, such as Kanesue Co. Ltd., could be kept fresh at home. This form of preservation has dictated the ever-growing importance of the cool chain until today, whereby in recent years the ta-kkyuu-bin lorries, which deliver fresh food from the countryside to urban areas, have introduced a new form of distribution, thereby questioning the technological logic of the post-war food chain.

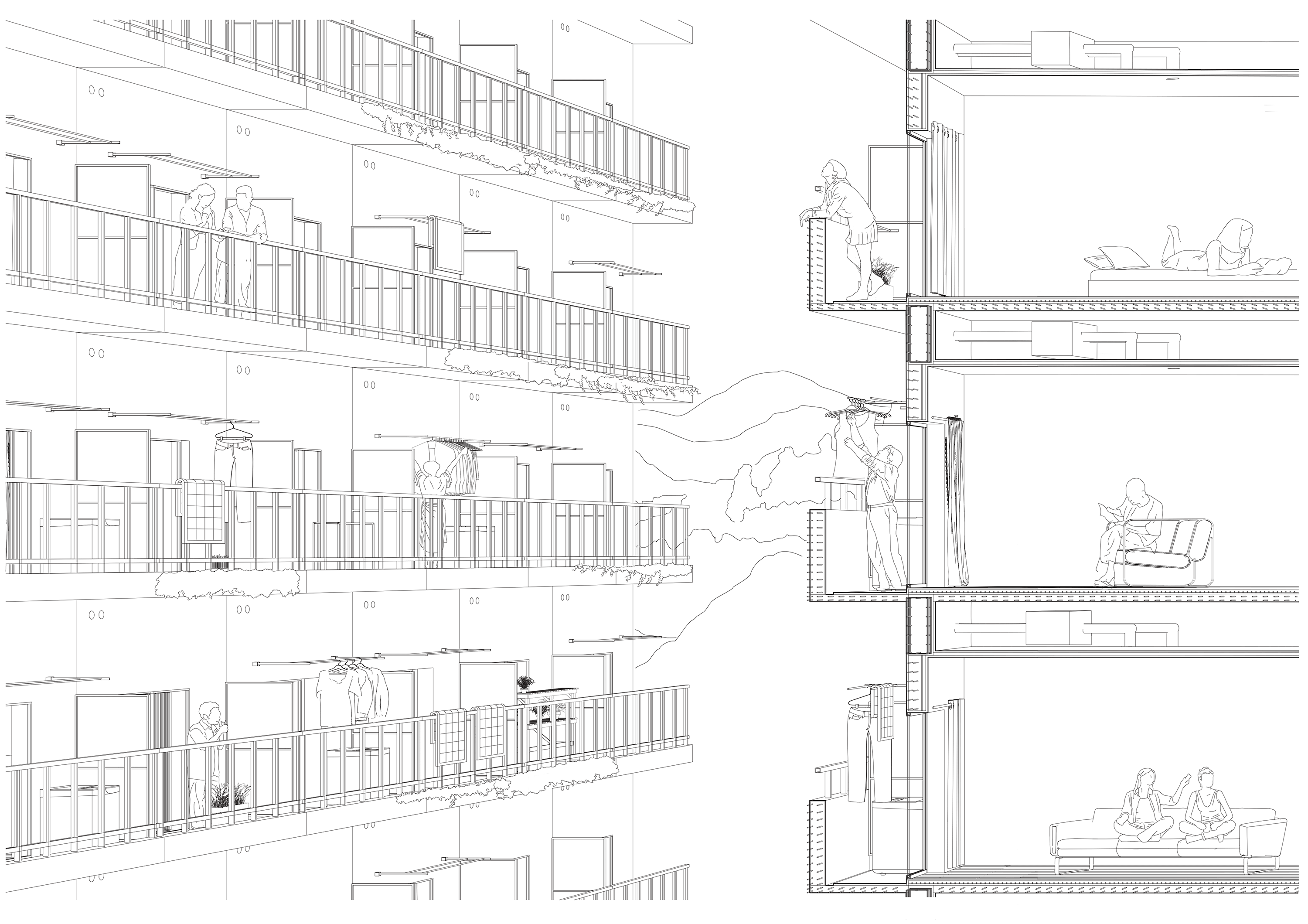

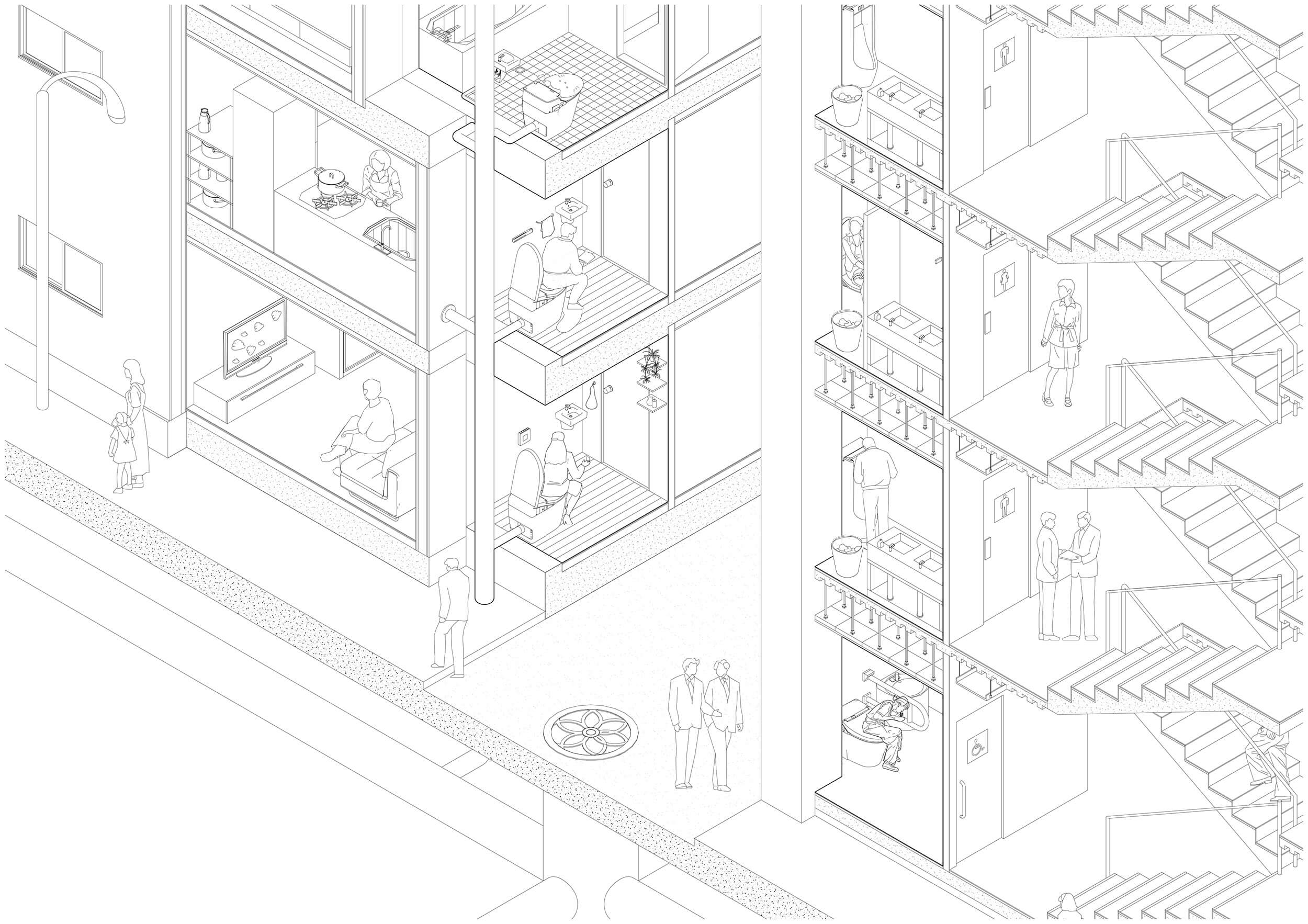

Partition

The history of the exterior partition-wall in the Japanese house seems to run in an opposite direction to the modern European one: from a succession of spatially differentiated thresholds to an overall technical ensemble. In the pre-modern period the building envelope was defined by its rich depth, which often embraced the entire house and its garden, forming a multi-layered and porous interaction between outside and inside. The enclosure of the post-war Japanese house, on the other hand, is reduced to a solid wall assembled out of mass-produced elements, leading to the collapse of the spatial multi-layeredness and its replacement by several functionally clearly delimited elements, namely the compact wall and its various openings, such as sash windows, air-conditioners, steam outlets, etc. In recent condominiums the wall has become defined by its increasing technological dependence, with a double, often contradictory goal: an ideal tightness of the enclosure and a series of highly controlled openings, gradually cutting off the inhabitants from their natural outside environment while creating a highly artificial one on the inside.

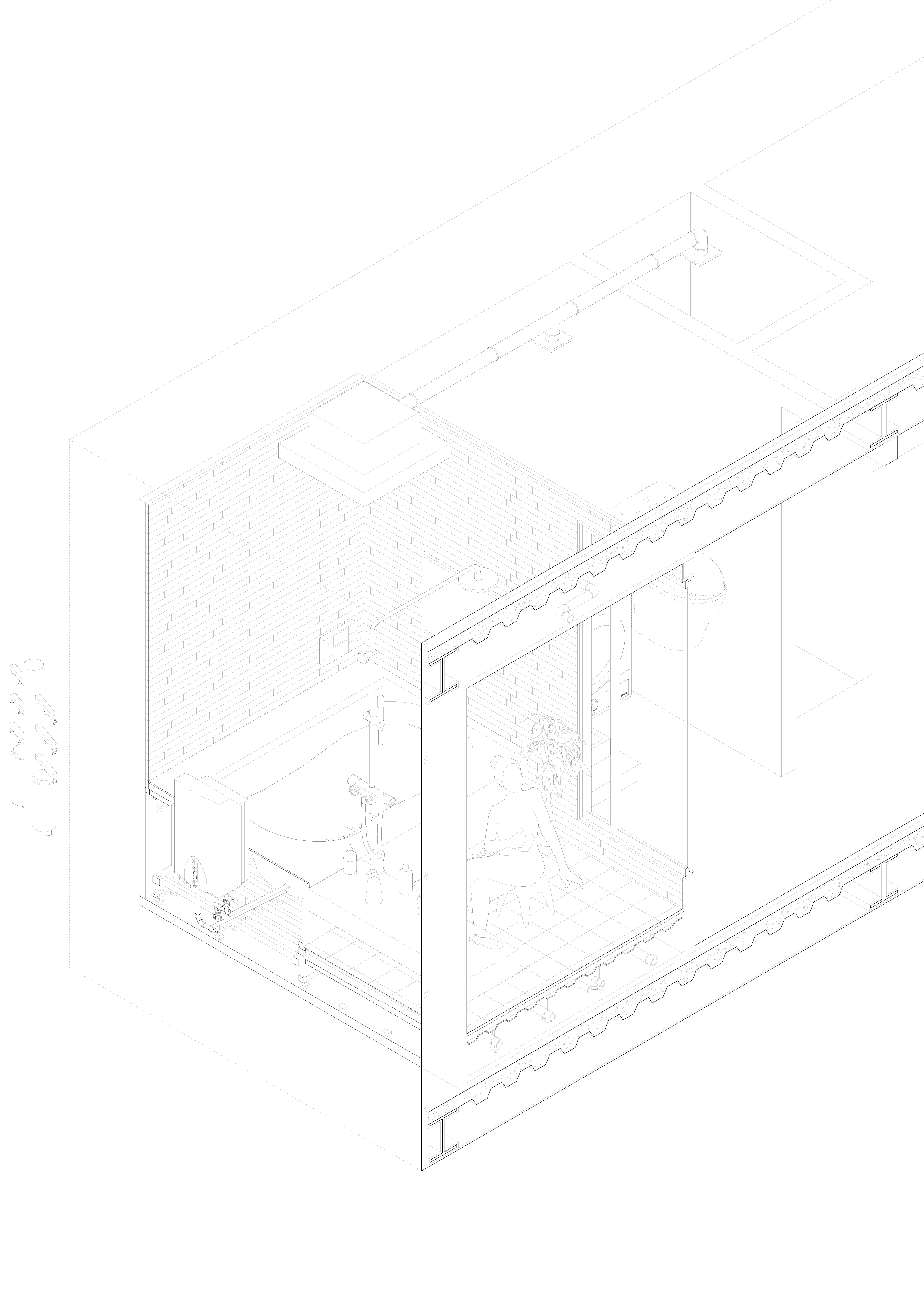

Bath

The research follows the transformation of the Japanese bath over the last 150 years from a set of portable objects – each designed for its respective distinct purpose yet not bound to a particular space – to a bathroom integrating the different elements into a whole unit, including the surfaces of the ceiling, the walls and the floors, as well as the hidden installations for water supply, water heating, sewage disposal, driers, lighting, and so on.

Originating as a service reserved to a privileged few – where the water was brought from the well by a servant, while another servant was responsible for heating it, preparing the bath and maintaining the right temperature – more so than with other devices and spaces in Japan, the history of the private bath is closely linked to social emancipation. In the post-war years the equipment of apartments with baths, facilitated by compact and safe gas-water-heaters, became a symbol of improvements in quality of life under the welfare state, while in more recent years the fully-equipped bath has more and more become a highly technological space of contemporary comfort and body-care, its surfaces imitating wood and tiles and thus, via associations, continuing to establish relationship to its origins, albeit an indefinite one.

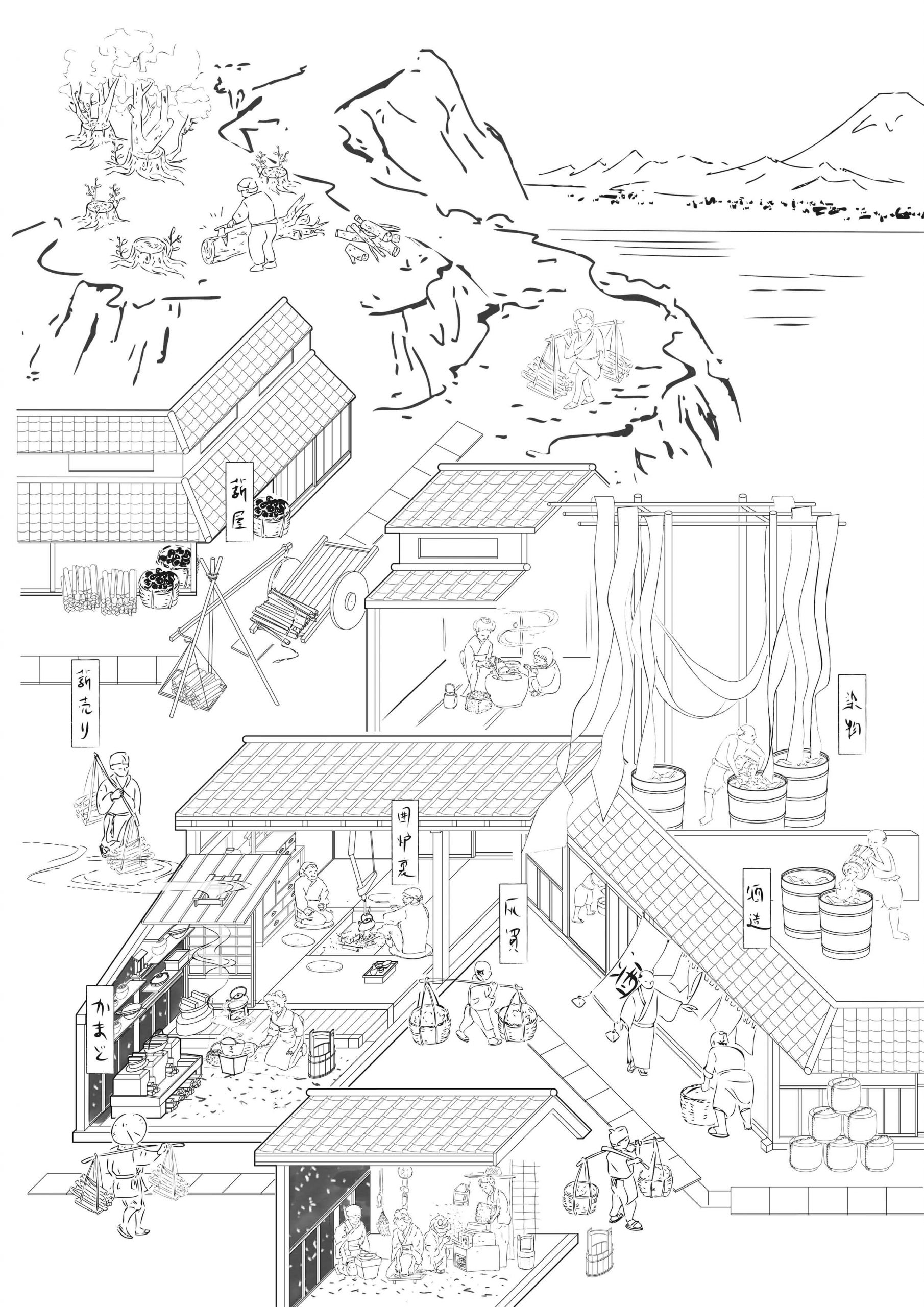

Stove

As a once archetypal household element, the stove has gradually become invisible in contemporary housing, with open-flame cooking disappearing into glasstop IH stoves and heating being concealed in the floors. Simultaneously the energy supply system has grown into an extensive and cohesive global network, at once distant and thus invisible to its end users yet heavily transforming the hinterland. Until the end of the nineteenth century the network was tangible and concrete: firewood was acquired from the forest, purchased by each household and used for the stove, and afterward the ash produced was re-collected by ash-traders for other uses such as sake brewing. From around 1960 Japan increasingly imported liquefied natural gas via tanker ships as an alternative energy supply, requiring a complicated gas-supply infrastructure, along with urban renewal, including shipyards, pipelines, gasometers, etc. Today the power system is a hybrid one, fed from multiple resources, including atomic power and renewable energy, making the network evermore extensive and abstruse.

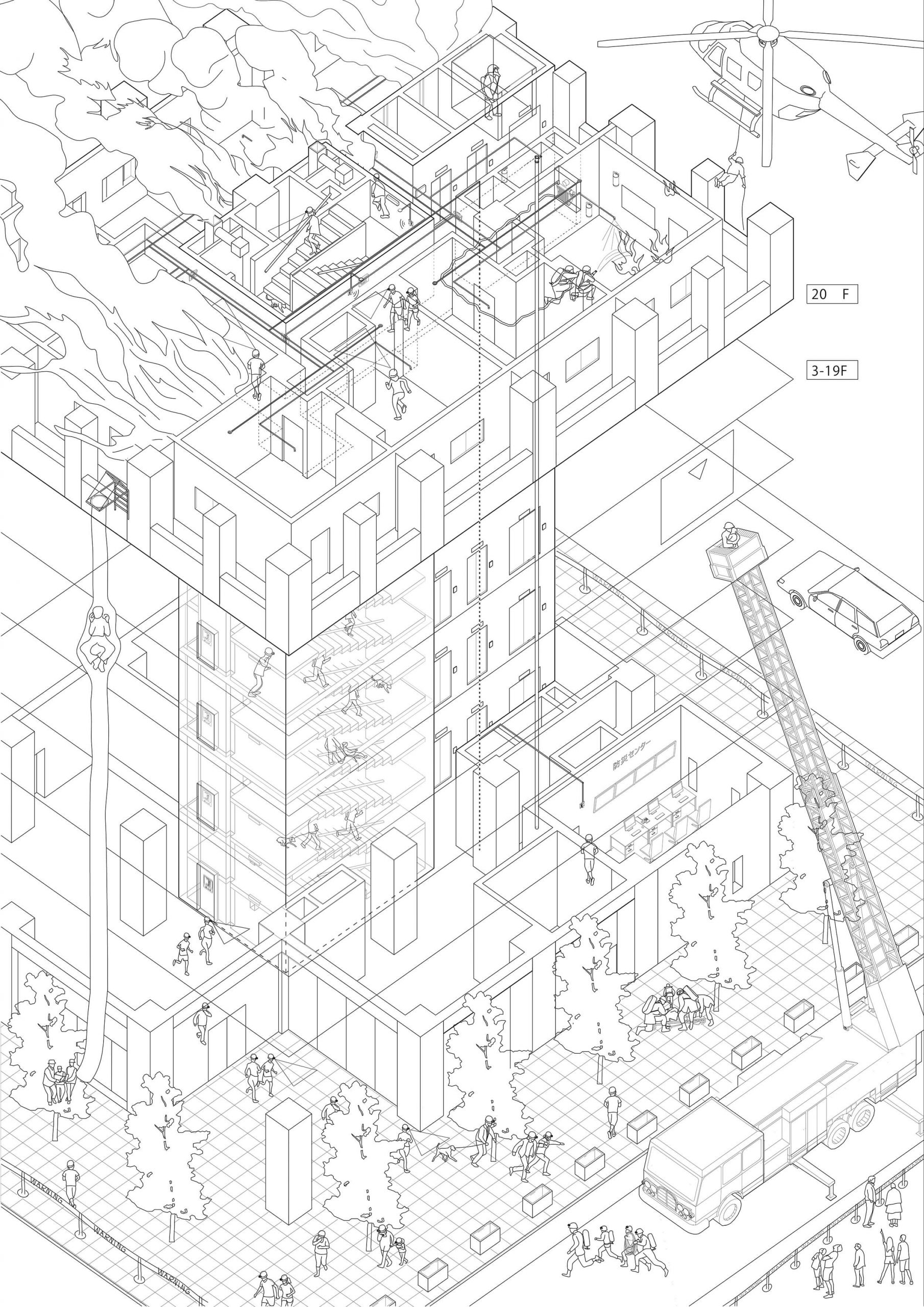

Staircase

From the Meiji Period to today the techniques of firefighting have shifted from the protection of a district, with large main streets or fire-resistant storehouses providing firebreaks, to en-masse fire-protected buildings, ensuring people’s ability to escape a conflagration. In the post-war period, with the densification of Tokyo, the vertical concrete staircases in multistory buildings—which themselves served as firebreaks along the main streets—became the major escape route, complemented by various types of devices that can be used from balconies or windows. In contemporary high-rises the common circulation system has become host to an entire emergency system, with smoke and gas detectors, alarms connected to ground-floor emergency centers, sprinklers, fireproof staircases, special emergency fire-fighter elevators, and even rooftop helicopter landing-pads.

Sink

While the shape and function of the sink has remained largely similar throughout its modernization, as a network it has greatly changed through time, perhaps most tangibly expressed in the reduction of the visibility of water in Japanese daily life. Even though water-supply systems were introduced within cities in the Edo Period, daily water management still entailed close human interactions: guarding the water source, lifting water from the well, common laundry activities, etc. Although the widespread introduction of underground water-piping systems and pumps after World War Two enabled the direct delivery of water to individual apartments, wastewater still remained open and thus visible. Further improvements in the closing decades of the twentieth century, in the form of pressure pumps, facilitated universal direct supply, even to multistory buildings. At the same time, grey water and black water are now systematically transported to treatment plants through a sewage system, hidden from sight, before being fed back into rivers or the sea.

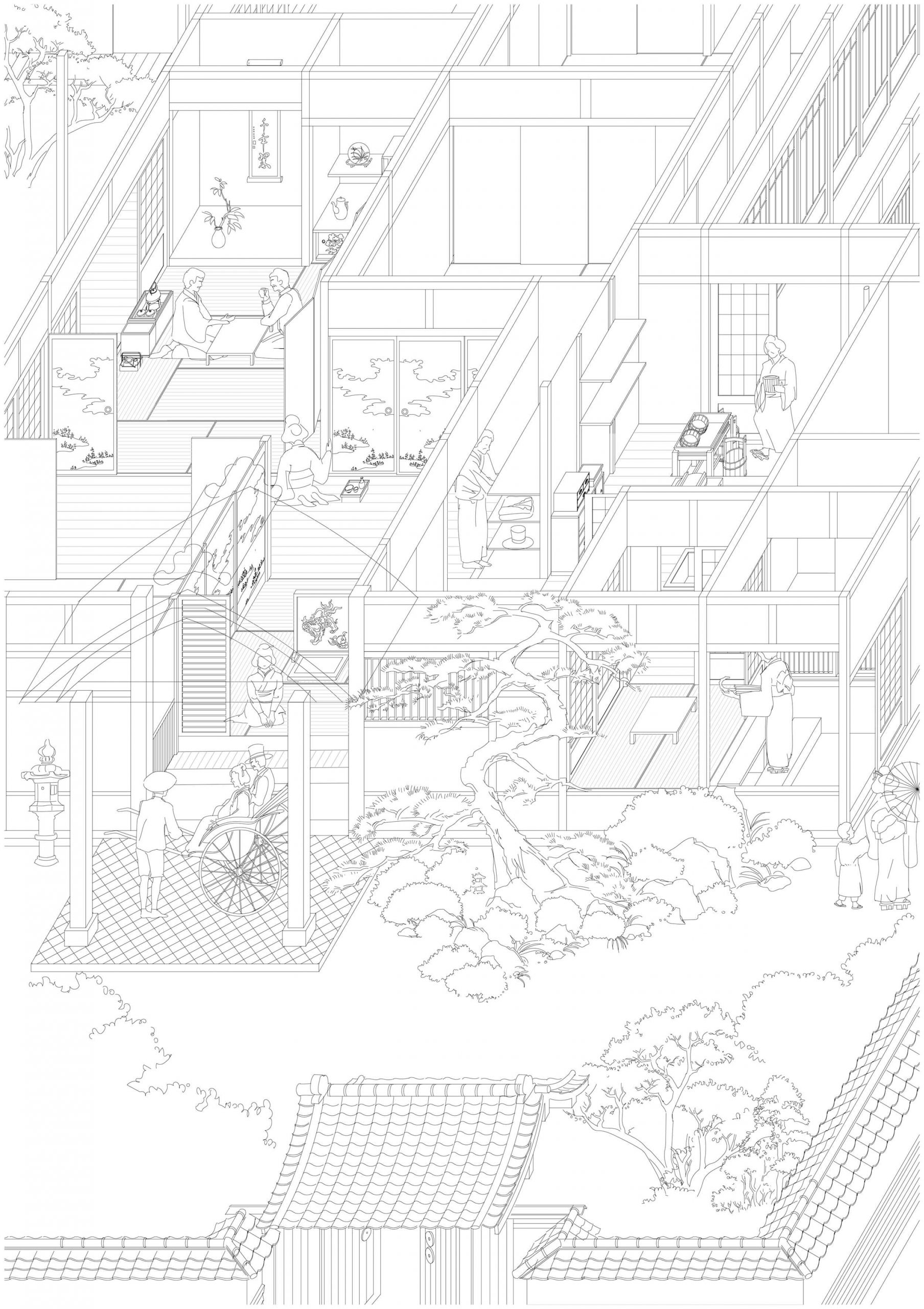

Genkan

From the Meji Period to today the genkan (a Japanese house-entry-cum-doormat) has evolved from a space of etiquette to a functionalistic space, and nowadays to a space of convenience. In the Meji Period a representative house had three entrances with a front genkan (表玄関), an inner genkan (内玄関), and a katteguchi (an outside connecting door) in the kitchen, reflecting the different social statuses of the master, family members, and servants. Etiquette required a long spatial sequence from the main entrance to the reception rooms, carefully designed and staging the best views to the garden. In post-war apartment houses the traditional design of the genkan was simplified to make it a compact space containing various functions such as storage, washing, receiving goods, or making phone calls. In essence it is designed as a public space inside an apartment. However, in contemporary high-rise residential buildings the boundary between the private interior and the public exterior has been overly stretched by the introduction of common entrance lobbies where guests can be welcomed on the ground floor. Moreover, a series of technical devices, such as cameras, sensors, automatic doors, elevators, and intercoms, have been introduced for security, accessibility, and comfort, again physically lengthening the distance to the private door to an even greater extent.

Toilet

The development of the toilet and the treatment of excrement in Japan are closely linked to a growing mechanization of the lavatory as a device and its progressive shift vis-à-vis the house from outdoors to indoors. In the Edo and early Meji Periods toilets were located at the edge of or outside the house. Conceived as a squat-latrine system, made out of wood, it was adapted for the easy collection of the excrement, which was then used as fertilizer. Between the World Wars, new systems, new materials, and even new toilets (for instance toilet bowls) were slowly introduced, while the collection of sewage became more and more mechanized, with basket collection being successively replaced by trucks, then mobile vacuum-extraction units, and later still by a Western type of sewage system with pipes. In recent years the predominant European-based device has become hyper-Japanized, highly automated (including washing, drying, background noise, cleaning, disinfecting, etc.), and even described and praised as something kawaii (cute, adorable) in the public narrative.